- What Is Heart Failure

- The “Heart Failure Syndrome”

- Signs and Symptoms of Heart Failure

- Hormonal Response to Heart Failure

- Major Hormones of Heart Failure

- The Heart Failure Syndrome Diagrammed

- Classification of Heart Failure

- Other causes of Heart Failure

- Diagnosing Heart Failure

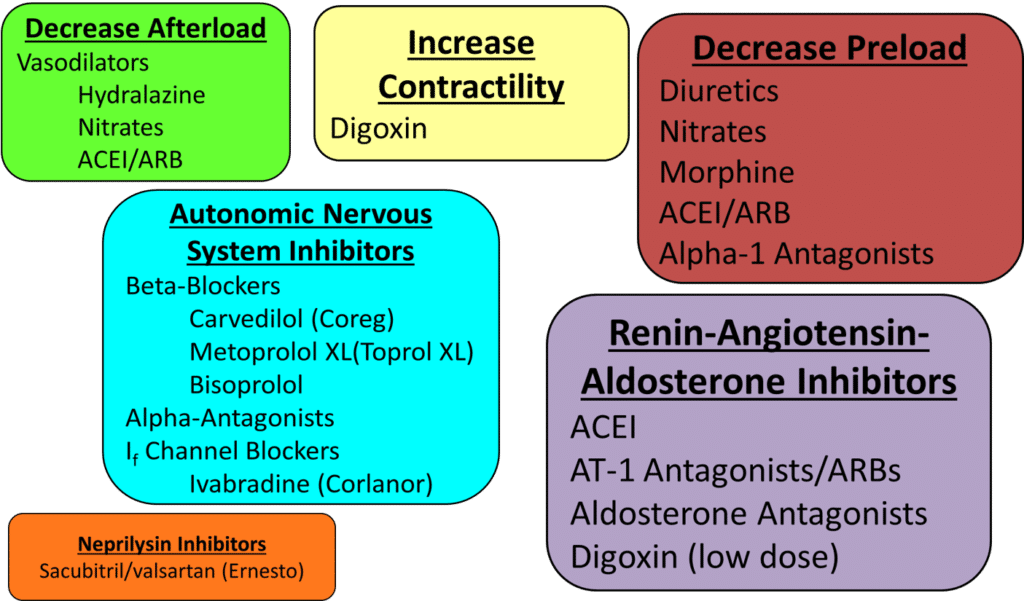

- Treatment of Heart Failure

- Conclusion

Heart failure (HF), also called congestive heart failure, is one of the most common hospital diagnoses and therefore is encountered by almost every medical specialty. This article summarizes and simplifies HF.

What Is Heart Failure

Although HF is a diagnosis upon itself, I view it as a clinical syndrome that always has another cause. As such, providers treat the symptoms associated with the syndrome, but must also look for a specific cause and then treat that cause.

The “Heart Failure Syndrome”

HF is a compilation of symptoms typically caused by the lack of efficient blood flow through the body. Subsequently, two major problems develop. The first is the lack of forward blood flow that fools the kidneys into “thinking” there is not enough fluid in the body. The kidneys respond by trying to retain sodium and hence fluid. Second, there is a backup of bodily fluid resulting in congestion. This is a cyclic process that can build on itself. The body responds using compensatory mechanisms, to improve blood flow and fluid status, but over time, these compensatory mechanisms overwhelm the body becoming dysfunctional and detrimental.

Signs and Symptoms of Heart Failure

The signs and symptoms of the “HF syndrome” are directly related to total body fluid overload and congestion. Patients may describe shortness of breath (dyspnea) that occurs with activity or at rest, orthopnea (the need to prop their head and chest up when lying down), or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (waking up and gasping for air). They may complain of fatigue, decreased exercise tolerance, cough, sleep disturbances, abdominal discomfort, abdominal bloating, anorexia, or early satiety. Additionally, patients commonly get edema (swelling) and acute weight gain.

Hormonal Response to Heart Failure

The body produces several compensatory hormones to combat HF. These include norepinephrine, angiotensin-converting enzyme, aldosterone, and several others. In the past, the only treatments available were geared toward augmenting a weak heart and to rid the body of excess fluid. These treatments help the patient’s symptoms, but overall do not decrease mortality rates. While this is still the initial treatment of HF, many long-term treatments focus on inhibiting the abnormal hormonal system (See HF Treatment below). Inhibiting these hormonal systems helps patients feel better, and live longer.

Major Hormones of Heart Failure

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine is a product of the autonomic nervous system and causes constriction of the blood vessels. Additionally, norepinephrine stimulates the heart and makes it beat faster. This initially helps blood flow, but later puts excessive stress on the heart.

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme/Aldosterone

Angiotensin-converting enzyme and aldosterone are part of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and cause constriction of blood vessels and retention of sodium and fluid. Again, this process initially helps the patient, but later becomes detrimental.

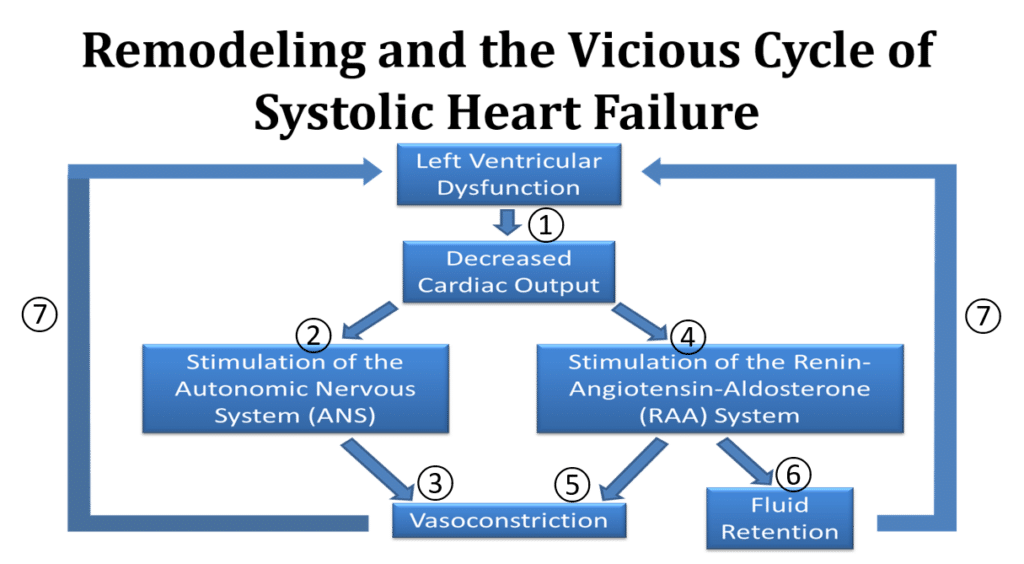

The Heart Failure Syndrome Diagrammed

Here is a visual diagram showing the HF process. In this case, a weak left ventricle causes the heart failure (Heart failure with a Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF) or systolic dysfunction).

- The weak heart decreases blood flow to the body leading to poor renal perfusion and congestion

- Stimulation of the autonomic nervous system and release of Norepinephrine

- Vasoconstriction (constriction of the arteries) occurs

- Stimulation for the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and release of Angiotensin-converting enzyme and aldosterone

- Vasoconstriction occurs

- Fluid retention occurs

- Additional strain is placed on the heart and the cycle worsens

Classification of Heart Failure

HF is classified in many ways. Examples include heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) vs. heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), systolic vs. diastolic, left-sided vs. right-sided, low-output vs. high-output, forward vs. backward, and acute vs. chronic. There are other classifications as defined by New York Heart Association Functional Class and The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Heart Failure Stages.

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) vs. heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)

HFrEF vs. HFpEF is currently the most common way to classify heart failure. This is very similar to the systolic vs. diastolic. This classification refers to left ventricular function. In general HFrEF (systolic heart failure) occurs due to weak heart muscle (poor contractility). HFpEF occurs due to the inability of the heart to relax and accept blood flow.

Systolic vs. Diastolic

See HFrEF and HFpEF above.

Left-slides vs. Right-sided

Left-sided heart failure refers to a weak left ventricle, whereas right-sided heart failure refers to a weak right ventricle. Left-sided heart failure is the most common cause of right-sided heart failure. With left ventricular dysfunction, there is a backup of blood flow to the lungs and body causing congestion and fluid retention. Additionally, the kidneys retain salt and water due to the decreased renal perfusion. Right ventricular dysfunction causes back up of flow to the body resulting in fluid retention, edema and ascites, and poor perfusion to the lungs.

Low Output vs. High Output

Low output heart failure is another way to say that flow to the body is hampered. Causes include a weak left or right ventricle, severe cardiac valvular abnormalities, constriction or restriction of the heart, and other things. With high output heart failure, the heart muscle itself is usually normal or hyperdynamic, but there is increased fluid or blood flow in the body causing fluid overload and congestion. Although this is called “heart failure” because the symptoms are exactly the same, the heart functions well. The three main causes of high output heart failure are chronic anemia, thyrotoxicosis, and Beriberi syndrome.

Forward vs. Backward

Forward heart failure suggests that flow out of the heart to the body is impaired. Backward heart failure suggests that flow into the heart is impaired causing blood flow to back up.

Acute vs. Chronic

Acute HF is when the signs and symptoms of HF develop rapidly, are new, or worsen. Chronic HF is after an acute episode is compensated.

Other causes of Heart Failure

There is a multitude of conditions that can also lead to heart failure. Some inhibit flow from the heart, some result in severe backflow, some cause constriction to the outside of the heart, some impair the heart muscle from working normally, and some just cause excess fluid within the body. Conditions include:

- Cardiac valvular abnormalities (narrowing and regurgitation)

- Tumors (within or outside the heart)

- Infections like sepsis or endocarditis

- High output conditions like chronic anemia, thyrotoxicosis, and Beriberi

- Infiltrative cardiomyopathies like amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, sarcoidosis, Wilson’s disease, and others

- Pulmonary diseases such as severe COPD, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary emboli

- Constrictive processes such as cardiac tamponade or constrictive pericarditis

- Acute and chronic kidney injuries

- Acute and chronic liver disease

- Myocardial infarctions

Diagnosing Heart Failure

Taking a thorough history and performing a detailed physical examination is the most important part of diagnosing HF. Providers will also obtain blood work, chest x-rays, and an electrocardiogram. Echocardiograms (ultrasounds of the heart) are the primary test for looking at cardiac function, although function may also be checked using nuclear cardiology imaging, or an MRI. Additionally, a stress test, heart catheterization (angiogram) or other test may be ordered to assess for blockages in the patients’ coronary arteries.

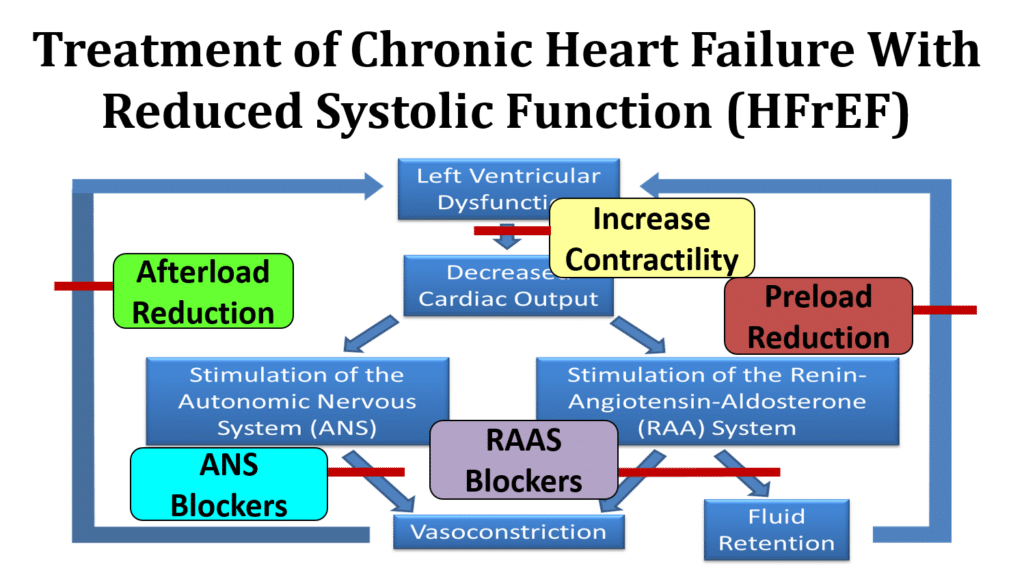

Treatment of Heart Failure

Treatment for HF is divided into acute treatment, and chronic treatment. Acute treatment addresses life-threatening conditions and gives immediate symptom relief. Chronic treatment addresses the underlying conditions that led to the HF in the first place (See the diagrams below).

Treatment for Acute Heart Failure

The goal of acute HF treatment is to get rid of excess fluid, promote adequate blood flow and organ perfusion, and support the patient’s vital signs. Additionally, providers must diagnose and treat acute, life-threatening conditions such as an acute myocardial infarction, cardiac tamponade, sepsis, etc. During this stage, the providers may identify who might benefit from revascularization and begin patient education. Since there is not just one approach, providers evaluate and treat each patient individually.

Acute Heart Failure Treatment Options:

- Oxygen

- Adjust the patients’ position

- Respiratory support (e.g. a ventilator if necessary)

- Preload reduction (decreasing flow to the heart)

- Diuretics, nitrates, opiates (e.g. morphine), acute dialysis

- Positive inotropic agents (medications that help the heartbeat stronger)

- Dobutamine, dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine)

- Phosphodiesterase inhibitors

- Afterload Reduction (reduce the pressure pushing back on the heart)

- Phosphodiesterase inhibitors, ACE inhibitors, Angiotensin receptor blockers, hydralazine

- Intraaortic balloon pump (IABP)

- Circulatory Support

- Left and right ventricular assist devices (VADs)

- Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO)

Some of these treatments may help the patient in multiple ways and fit into more than one category above. More options exist.

Treatment for Chronic Heart Failure

The first thing is to maintain patient stability by keeping them “dry” and maintaining adequate breathing. Simultaneously, The provider addresses the underlying condition(s) that caused the HF. Goals include increasing longevity, eliminating symptoms, expanding exercise capacity, assuring an adequate quality of life, and educating.

Chronic Heart Failure Treatment Options

- Revascularize patients with severe obstructive CAD that is causing a weak heart.

- Control abnormal blood pressures

- Hormone inhibition in patients with a weak heart

- Beta blocking agents, angiotensin-c0nverting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), aldosterone inhibitors, and neprilysin inhibitors

- Support a weak heart

- nitrates/hydralazine, digoxin

- Cardiac resynchronous therapy (CRT) with or without a defibrillator [special pacemaker that also may be able to shock the heart out of dangerous arrhythmias]

- Others

Remember there are a lot of possible underlying conditions and each may have its own set of treatments.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that heart failure is really a syndrome consisting of signs and symptoms from fluid overload within the body. The acute phase of HF is treated by addressing the life-threatening conditions, fluid overload, and providing immediate symptom relief. Always search for the underlying cause of heart failure and treat it, too.